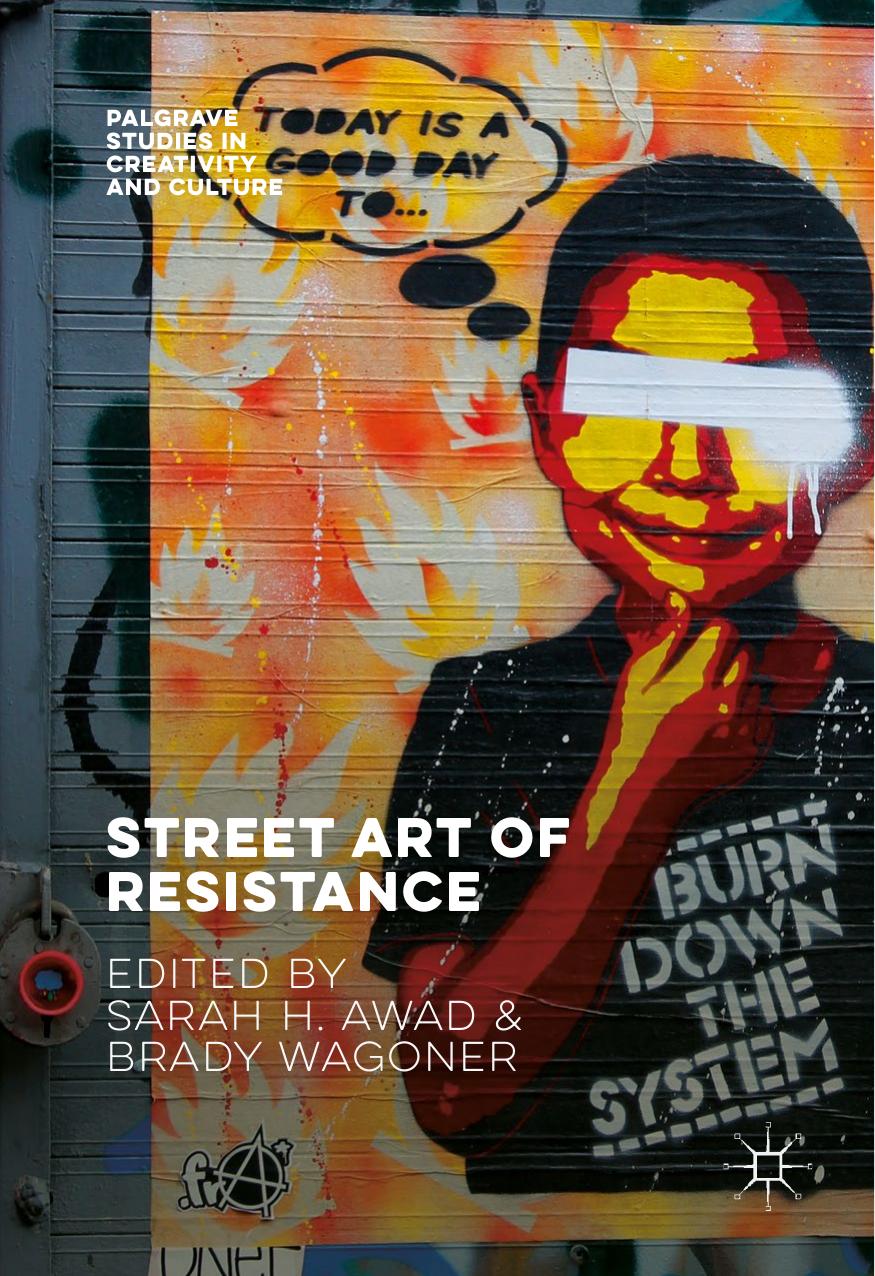

Street Art of Resistance by Sarah H. Awad & Brady Wagoner

Author:Sarah H. Awad & Brady Wagoner

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Springer International Publishing, Cham

The Constitutive Other: Murals as Artifacts of a Connected History?

As illustrated above, in Belfast, the murals tell the story of a troubled and violent past, justifying and actualizing the sectarian divisions in the present. In this sense, they are not only representations of the past, but rather a mechanism of identification that denotes the inability to coexist in any other way than through the division and opposition between the two communities (Jarman, 1997, 1998; Jarman & McCormick, 2005; Rolston, 2003, 2004).

According to Bill Roslton (2003, 2004), the major themes that characterize the Protestant–loyalist–unionist murals have been six: the historical celebration of the victory of King William of Orange (Photo 1); the painting of flags and other traditional symbols celebrating the Commonwealth; the celebration of Britain’s imperial image (including the bleeding hand of Ulster—one of the few common symbols used by loyalist and republicans alike); the commemoration of historical events; images that promote paramilitary activities (Photo 3); and, finally, images that lament and victimize the losses during “The Troubles.”

On the other side, the major themes that have characterized the Catholic–nationalist–republican murals are those linked to the hunger strike of 1982 and previous forms of protest of political prisoners, military images representing IRA members as challenging fighters or victims, electoral propaganda, and elections results, and historical themes in relation to the independence of Ireland and with reference to the Gaelic mythology (Photo 2). The murals often recall the repression and discrimination suffered by the community, as well as their resistance to the British state repressive dynamics. Lastly, these murals equate the republican cause to other struggles for self-determination across the world, including Palestine , the Basque Country, and South Africa (Rolston, 2004).

Similarly, both communities activate history through a militarized and victimized past. There is a third way of looking at today’s murals, one that incorporates historical narratives of both groups under the external gaze of an outsider, a foreign other to the conflict , yet its complicit witness: the tourists. According to Jarman (1998) the murals began to appear in the Rough Guide of Belfast in 1992. Today the murals are objects of consumption, instruments of rehabilitation of a conflict that remains present albeit in a commodified form (McDowell, 2008). The murals retain a seductive effect: observing them is a secure way to become familiar with a violent and dangerous trajectory of contending political identities and projects; an experience otherwise ungraspable in the daily life of the majority of the visiting population. Today, most tourists visiting the city will join the seething business of “conflict tourism ” (Jarman, 1998; McDowell, 2008).

As you can see in Photo 4, black cabs and their guides are promoted as exclusive attractions of the city. Often former paramilitary fighters of both communities acts as specialised city guides, these guides organize a variety of circuits for all possible tastes and political inclinations.9 Any search on the Internet will show you various tour possibilities, and various tourists posing in the streets of Belfast with the black cab and the mural as a unique attraction of the city.

Download

Street Art of Resistance by Sarah H. Awad & Brady Wagoner.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Should I Stay or Should I Go? by Ramani Durvasula(7641)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(6686)

Fear by Osho(4723)

Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi(4671)

Rising Strong by Brene Brown(4435)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(4421)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4356)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4340)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4323)

Lost Connections by Johann Hari(4164)

He's Just Not That Into You by Greg Behrendt & Liz Tuccillo(3873)

Evolve Your Brain by Joe Dispenza(3653)

The Courage to Be Disliked by Ichiro Kishimi & Fumitake Koga(3473)

Crazy Is My Superpower by A.J. Mendez Brooks(3380)

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(3366)

Resisting Happiness by Matthew Kelly(3331)

What If This Were Enough? by Heather Havrilesky(3298)

The Book of Human Emotions by Tiffany Watt Smith(3284)

Descartes' Error by Antonio Damasio(3263)